The Illusion of Clarity: Why Smart Teams Talk Past Each Other

Understanding the psychology behind miscommunication and how to bridge the gap between what we say and what others hear

I recently had a discussion at work where I was certain that we were on the same page. I didn’t even think for a second that there could be a misunderstanding. Then I heard from a colleague commenting the decision which was made, which very much confused me as I was under the impression that we decided something else. I do believe I communicate clearly, but reality is that we can all perceive the same thing in different ways.

Miscommunication isn't always obvious; it creeps in through subtle gaps. A friend's "I think this is okay" when asked about dinner plans is heard as enthusiastic approval, when it was really ambivalence. A partner's silence after discussing weekend commitments is read as agreement, when in fact they're quietly concerned about the time commitment.

Why do these gaps between intent and impact happen so often, even among talented teams? As a psychologist working in tech, I've learned it usually comes down to a few surprisingly common psychological phenomena.

The Illusion of Transparency: Your Intent Isn't as Obvious as You Think

Have you ever been sure your team understood your message, only to find out later they didn't? The illusion of transparency is to blame. It's a cognitive bias that leads us to overestimate how much others can read our thoughts or emotions. In other words, we believe our intentions are crystal clear, when in reality they're not.

Psychology research confirms this: public speakers often think their nervousness is obvious, yet audiences report barely noticing it. We feel internally transparent, but others just don't see as much as we imagine.

We forget that others don't have the same context or emotional insight that we do. A product leader might think a concern was clearly implied by their tone or a slide's emphasis, but unless it's clearly stated, the team may completely miss it.

Research refers to this as an egocentric bias: we're so anchored in our own perspective that we misjudge what's obvious to others. In product development, that means features get built under false assumptions. The PM thought the risk was transparent; the team only saw green lights. The result? Surprise and disappointment all around.

The first step to closing the gap is realizing that our colleagues aren't psychic.

The Curse of Knowledge: Trapped in Our Own Perspective

This one is one of my favorites and one that I very frequently have to remind myself of when doing trainings. It's aboutthe curse of knowledge. Once you know something, it's hard to imagine others not knowing it. We've all been on both sides of this. An engineer dives into explaining a complex architecture, peppering the conversation with acronyms, assuming everyone is up to speed. Or a designer insists a workflow is intuitive, forgetting that they lived in the design for weeks while the developer just met it today.

When we become experts on a topic, our explanations shorten. We skip details, use jargon, and speed through basics that are painfully obvious to us and completely confuse to our audience.

One classic experiment illustrates this bias. A researcher at Stanford asked people to tap out the rhythm of a well-known song (like "Happy Birthday") and predict how often listeners would guess it. The tappers predicted about 50% of the time; in reality only 3% of listeners guessed correctly. Why the huge gap? Because the tappers heard the song in their head (full melody and lyrics) and couldn't imagine the listeners' perspective of just hearing disjointed taps. The knowledge of the song "cursed" their ability to communicate it.

In our teams, each role hears the full music of their own domain. Similarly, we assume what's obvious to us will be obvious to others, but it's not. As the tapping study concluded, people "frequently assumed that what was so obvious to them would be equally obvious to their audience."

For me, it's been around design processes and research methods where I assume that more is known than it actually is the case. This often leads to me underestimating how much time training workshops will take and thus having to speed through certain parts as I do not reserve enough time for explaining things properly.

Over time, these little misunderstandings compound. The curse of knowledge makes us bad at explaining, and even worse at realizing we weren't understood. We assume shared knowledge that simply isn't there.

If you've ever left a meeting thinking "why didn't they get it? I explained it so well," there's a good chance the curse of knowledge was at play. The more experience and information we have, the more careful we must be to meet others where they are. As a rule of thumb: if something seems obvious, spell it out anyway. Your "obvious" might be novel to someone else.

Evolutionary Mismatch: Modern Communication, Stone-Age Brains

Beyond specific biases, consider the context in which our communication happens. Modern work is filled with Slack pings, emails, Jira tickets – channels stripped of the rich non-verbal cues humans evolved to rely on.

Our brains spent hundreds of thousands of years adapting to communicate in person, in real-time, with people who shared our immediate environment. That's our default wiring. Now, we're trying to coordinate complex projects with teammates halfway around the world, often through text on a screen. No wonder things get lost in translation.

This is also one of the reasons I love such tools as Loom, where I could record an explanation and show some visuals. It includes non-verbal cues, and a more holistic explanation can be made.

Research confirms this gap. People consistently overrate their ability to communicate effectively over email, not realizing how much meaning is not getting through. In one set of experiments, senders thought their sarcasm or humor was obvious, but receivers misunderstood the tone completely. The senders assumed the recipients "got it" (after all, they could hear their intended tone in their head), illustrating both the illusion of transparency and curse of knowledge in action. In reality, the crucial signals, voice inflection, a smirk or smile, a furrowed brow – never made it through the wire.

Additionally, in modern teams, we often lack shared context. Unlike a small village or a tight-knit office where everyone experiences things together, today one team can have members in San Francisco, Munich, and Bangalore each living in different contexts. When I mention "the market issue from last week," it might mean something totally different to a colleague who wasn't in that firefight with the customer.

Our evolutionary instincts assume a lot of common ground that isn't there. We think others know the backdrop, but remote and distributed work means they often don't.

This evolutionary mismatch shows up as misunderstandings and even conflict. Minor miscommunications that would be instantly corrected by a puzzled look in a meeting room now fester in silence. The lack of non-verbal feedback – those nods of understanding (or confused frowns) is like flying blind. We only realize we weren't on the same page when the deliverable comes in, off target.

It's critical to recognize that the medium and context we communicate in can amplify misinterpretation. Given this, we have to be extra intentional about checking understanding. A quick video call or a "just to confirm, you mean X…" can save weeks of downstream frustration. As the communicator, I actively look at the facial expressions of my audience and try to understand if I see any confused or concerned looks. If I do, I try to ask politely, "I see that you seem confused. Is there anything that I can explain better?" This can be done in an elegant and diplomatic way without putting the person on the spot. This is, of course, a skill that takes time to master, but even just being conscious of it is a fantastic start.

Hidden Differences: Mental Models by Role

So far, we've talked about biases that affect any human communication. But there's another layer particular to product teams: we each come in with different mental models.

A mental model is essentially the internal picture or framework you have about how something works. It's shaped by your expertise, experience, and even your role's incentives. In a cross-functional team, a product manager, a designer, and an engineer might look at the exact same feature and have three very different mental models of what success looks like.

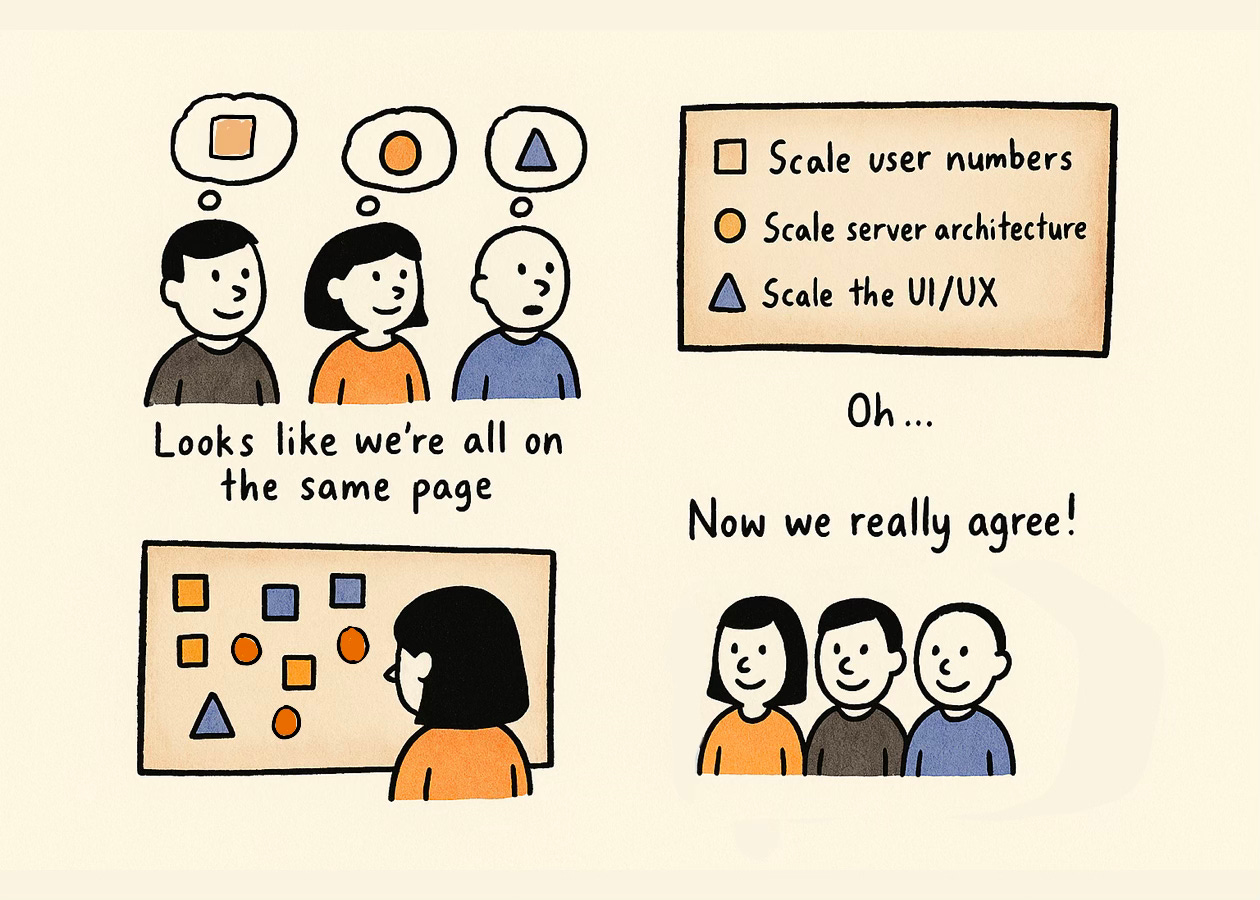

When I say to the team, "We need to scale this product in Q4," notice how ambiguous that is. In my product manager mind, we might envision scaling usage numbers and market reach. The engineering lead hears "scale" and immediately thinks of technical architecture and whether our systems can handle 10x traffic. The designer hears it and considers how the UX can scale to accommodate more features or users.

Each person nods, thinking they agree on "scale," but each is picturing something different! Later, when engineering invests time in backend optimizations instead of new features the PM expected, friction emerges. We were using the same words but speaking different languages.

These divergent mental models are a hidden source of misalignment. Mental model mismatches are sneaky, unlikeobvious differences (like one person says "yes" and another says "no"). On the surface everyone agrees, but under the hood they have different assumptions.

I often ask teams I work with to define a simple term like "MVP" (Minimum Viable Product). The definitions I get from each role are wildly different. One group says "MVP means the smallest set of features to get user feedback." Another says "No, it's the version of the product that's ready to sell." Yet another thinks it's a throwaway prototype. Imagine the chaos if they hadn't compared notes.

This is why creating a shared mental model is so important. Studies in organizational psychology have shown that teams with aligned mental models perform better and coordinate more effectively. When everyone shares an understanding of the goals, the user, and the plan, execution flows. When they don't, you get confusion and blame ("I thought you were handling that!").

The key is to surface these assumptions and make the implicit explicit. You might be thinking, "Sure, that sounds nice – but how do we actually do that in the middle of a busy product cycle?" One practical tool I've found incredibly effective is what I call the Assumption Mapping Exercise.

Assumption Mapping: A Framework to Reconnect Understanding

To bridge the gap between intent and impact, we need to actively create shared understanding. You can use theAssumption Mapping Exercise, a simple 3-step framework, with teams to get all those hidden cards on the table. It's like a spring cleaning for your team's collective mind.

Here's how it works:

Document Individual Assumptions – First, have each team member take a few minutes to write down their core assumptions about the project or issue at hand. This can include assumptions about the users, the goals, what "done" looks like, constraints, or terminology. It's crucial everyone does this independently at first to get the unfiltered view from each mind. For example, ask everyone to write what they believe the primary user goal is, or what "MVP" entails, before any discussion. This step often yields a surprisingly diverse list of "truths" that people assumed were shared.

Map and Compare as a Team – Next, bring everyone together (in a room or virtual whiteboard) and map out these assumptions side by side. Then, group similar ones, highlight contradictions, and note gaps. You might create clusters on a whiteboard: things everyone assumed in common vs. things only one person assumed.

This could visually look like a Venn diagram or a mind map. You might use colored sticky notes for each role (product in blue, design in green, engineering in yellow) and stick all assumptions up. Quickly patterns emerge – maybe all the yellow notes cluster on technical risks that others didn't even mention. This is the "aha!" moment where hidden misalignments become visible.

Identify Gaps and Build Shared Language – Finally, discuss the differences. Where did we assume the same things? Celebrate those, because it means some implicit alignment exists. But more importantly, where did we differ? Each difference is an opportunity to clarify and create a shared language.

Maybe the team had different definitions of "launch-ready". Now you can agree on what it means going forward. Maybe engineering assumed a certain solution was off-limits due to tech constraints. Now product can address that.

As a team, decide on resolutions for each major assumption gap. Agree on one approach, or at least acknowledge the uncertainty and decide how to resolve it (e.g. do research, get data, etc.). By the end of this exercise, you collectively author a new shared understanding document or diagram. This could be as simple as a written list of agreed assumptions and definitions, or a visual map of how you all see the problem now. The goal is a common reference point – our team's mental model for this project.

Assumption mapping takes the abstract and makes it concrete.

Implementation Tips: You might be thinking, this sounds time-consuming – how do we fit it in? In practice, it can be done in as little as 30-60 minutes and will save far more time by preventing needless rework.

I recommend using assumption mapping at key moments: project kick-offs, when starting a major feature, or whenever you sense "we're not on the same page." It's also great in retrospectives if something went wrong. Map out what everyone was assuming and find where the breakdown occurred.

To keep it efficient, constrain the scope. Map assumptions on one focal question at a time ("What problem are we solving?" or "Who is the user?" or "What does success look like?"). Use a timer for the individual write-down (5-10 minutes) and then spend 20 minutes mapping and 20 discussing.

Crucially, the linchpin of this exercise is psychological safety. People must feel safe admitting what they assumed or didn't know. As a facilitator, I set the tone by framing assumptions as neither right nor wrong. They are simply points of view. I encourage a curious mindset: "Oh interesting, I hadn't thought of it that way" instead of "How could you think that?"

If you're a team lead, consider sharing one of your own flawed assumptions first, to signal that it's okay to be vulnerable. When disagreements surface, remind everyone: you're all on the same team trying to make the product great. The goal is shared understanding, not debating who was "more right."

It's also a living artifact. As assumptions change or get validated, update the map. Over time, you'll find the team's thinking converges more and more in the shared center of that diagram.

It's amazing how many "Doh! I wish we'd known that earlier!" moments you can prevent with this simple exercise. I frequently do this exercise when kicking off research projects to identify the assumptions the team and stakeholders have regarding what we know is true and what we believe is true. And it's always satisfying to see the differences.

Closing the Gap: Intent and Impact Aligned

Misunderstandings will always be part of working with humans, we're wonderfully imperfect creatures, not robots. But as we've seen, being aware of the psychological traps (like assuming we're understood when we're not) and the unseen differences (like varying mental models) goes a long way.

Instead of defaulting to "ugh, they just didn't listen," we can approach team communication with a bit more humility and curiosity. Often, miscommunication isn't a lack of intelligence or effort – it's a lack of shared perspective. The gap between intent and impact can be narrowed.

As product and tech leaders, we set the tone. We can admit when we weren't clear. We can foster an environment where asking "Can you rephrase that?" is seen as a strength, not a weakness. The payoff is huge: fewer costly misfires, faster execution, and a team that actually enjoys working together because they get each other.

Our brains may not have evolved for calls and Slack threads, but with a little effort, we can adapt our processes and habits. I call you to action to try the Assumption Mapping Exercise with your team. Maybe in your next planning meeting or design review, take that extra bit of time to map out assumptions or simply discuss "What do each of us think X means?" You might be surprised by what you uncover.

It's a small investment for a potentially massive reduction in ambiguity. Over time, you'll notice the gap between what you intend to communicate and the impact it has gets smaller and smaller.

Ultimately, teams that master these skills become virtually miscommunication-proof. They develop an intuition for each other's thinking. That's when you achieve that almost mythical alignment where product, design, and engineering operate as a seamless unit, building the right thing in unison.

It's possible to connect (and disconnect), and it starts with understanding the psychology. So in your next team interaction, remember: you're not an open book, your knowledge can blind you, and your brain misses old-school cues – and that's okay. With awareness and tools like assumption mapping, you'll ensure that what you mean is what gets heard.

After all, the smartest teams aren't the ones with the fewest disagreements. They're the ones who know how to find clarity amid the chaos.

Ready to put this into practice? In your very next team discussion, set aside a few minutes to verify one key assumption. Ask everyone to write down what they think the main goal is (or who the primary user is, or what "done" means), then compare.

That's it. Break the ice. Spark the conversation. You'll take a powerful step toward aligning intent with impact. And once you see the benefits, I suspect you won't want to work any other way.